Graded absolutism: the moral framework taught by Jesus, and you probably haven't heard of it

There are a few big moral frameworks. You’ve got consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics, social contract ethics, and the internal moral compass (axiological ethics). The Wikipedia article on graded absolutism is the shortest. Graded absolutism is mentioned once, in passing, in the page on morality; it isn’t mentioned at all in the page on ethics, or in the page on Christian ethics.

I’ll argue that none of the other moral frameworks are sufficient, and that Jesus is a graded absolutist. This moral framework was the driving force behind Christ’s critique against the Pharisees, and it’s as relevant today as ever before.

But before we get into graded absolutism, why is every other moral framework worse? Once we get to graded absolutism, expect a sharp turn to the religious. After all, I have an axe to grind.

Social contract

Social contract morality is a good starting point. If you mainly want to get along with your group, this is a practical way to look at your morality. However, the social contract theorist doesn’t care if his tribe is eating babies as long as everyone else is doing it. But if you’re a social contract theorist and you run into a much bigger tribe that doesn’t eat its young, now you’ve got a bit of a problem. They are disgusted by your tribe’s practices and hold you in contempt. They conquer the land you’ve had for generations and they feel bad about it because your tribe is composed of immoral baby eaters.

If your primary concern in regard to morals is consensus, then there’s no such thing as moral decline, or moral progress. As long as everyone agrees on the rules, we should be ok. You can believe in social contract if you believe the mechanisms that lead to consensus are good and right. Suppose you believe most people are naturally good. If so, whatever the majority believes is therefore also right.

But we aren’t relativists. We believe that US after slavery was better than the US before slavery. In practice, most of us are moral relativists up until something gets under our skin, or we learn from bad consequences.

Consequentialism

Consequentialism argues that what is right or wrong depends on the results. It’s transactional. If a bigger tribe conquered you, then they’re right. Consequentialism doesn’t care about feelings. If you’re helping your neighbor, but gritting your teeth throughout, then you’re doing good. But we have to admit that bad things do happen to good people. And if consequences are your metric, they must not have been doing good.

Deontology

This bring us to deontology which says what’s right and wrong depends on rules and not the outcomes. An act is good regardless of the consequence. This does create a bit of problem because then we have to ask where these rules come from. A deontologist accidentally introduces a bad moral rule, they don’t have a mechanism to remove it or update it. And where do these rules come from anyways? Do they come from God? Are they innate? Or maybe the best we can do is live by a set of rules that aren’t self-contradictory.

When you do come up with rules, you run into a problem when you’re forced to choose between them. What do you do about the Nazi at the door? Do you lie to him about the Jews in your basement? Do you instead decide that it’s always moral to tell the truth?

Consequentialism, reformulated

Consequentialism also shouldn’t be disregarded so easily. If “speaking the truth” gets you in trouble, you’ll be able to learn that maybe you got in trouble because you were patronizing about it. The deontologist would need a rule against being patronizing. But that’s clearly silly, right? Do you really need a rule for that? And do you need a specific rule that tells you it’s ok to lie to the Nazi at the door?

If the Earth gets wiped out by an asteroid, it won’t matter whether or not you ate meat, if you cleaned your room, helped grandmas cross the street, etc. It’s not that doing these things is wrong, but if you’re an astrophysicist and a deadly asteroid is coming toward the earth, I’d want you to be a consequentialist.

Consequentialism can’t be everything, though. In the Cain and Abel story, the good guy dies. Why? If a person who sometimes defects is up against a person who never defects, the game theory is pretty clear. So doing good might just result in the bully always taking your lunch money. As a consequentialist, you’ll find a way to live another day, even if it means you have to deceive the bully, right? Still, it’s at least a little odd to have a moral framework that places moral blame on the victim.

Internal compass

We can say morals come from an internal moral compass. This, plus the constraint of non-contradiction is something close to what a lot of people believe. Many don’t look for a complicated moral framework to decide right from wrong. We often feel it in our bones when something is unjust.

But innate morality doesn’t get us all the way either. Again, we can’t go without consequentialism. Unintended consequences are everywhere:

“Passenger-side airbags in motorcars were intended as a safety feature, but led to an increase in child fatalities in the mid-1990s because small children were being hit by airbags that deployed automatically during collisions. The supposed solution to this problem, moving the child seat to the back of the vehicle, led to an increase in the number of children forgotten in unattended vehicles, some of whom died under extreme temperature conditions.”

“Drug prohibition can lead drug traffickers to prefer stronger, more dangerous substances, that can be more easily smuggled and distributed than other, less concentrated substances.”

“The use of precision guided munitions meant to reduce the rate of civilian casualties encouraged armies to narrow their safety margins, and increase the use of deadly force in densely populated areas.”

All the above are quotes from the Wikipedia post on unintended consequences. If you have homeless people in a wealthy country, it definitely doesn’t feel just. Shouldn’t we house them? Sure, but what if they’re on drugs? We don’t want to enable them, right? Should we force them into drug rehabilitation centers then? Is it justified to use force against someone who’s out of their mind?

We shouldn’t ignore our internal compass, but we shouldn’t believe our intuitions uncritically.

Virtue ethics

Virtue ethics aims for balance, rather than a set of rules, or mere consequentialism, or social contract. It’s also more prescriptive than just following your internal compass.

Instead having a moral absolute, you have the virtue of courage. Go too far in one direction and you’re rash and irresponsible. Go too far in the other and you’re a coward. It’s bad to be shy and bad to be boastful.

It’s hard to disagree with virtues. What does virtue say about the Nazi at the door? You’ve got multiple virtues. Sure, you could tell the truth. But being courage and empathy are also virtues.

However, it’s often hard to know if you’re doing too much or too little, which I’ve also written about here. According to Zizek, if you risk it all for a business and succeed, you’re courageous. If you fail, you were foolishly pissing against the wind.

Some more examples:

We lost the war because we didn’t give it our all. We shouldn’t have fought at all and just given in. So many lives would have been saved.

A kid who can’t swim is thrown into the pool. He starts flailing. Is he flailing too much or not enough?

Do I lack commitment? Or do I instead commit too readily and so end up giving up again and again?

Virtue ethics doesn’t tell you what you should and shouldn’t do. This gives it some valuable flexibility. It’s also useful for describing the reason for outcomes after they’ve happened. Some people have great ideas that they don’t execute on. Criticizing them for lacking the virtue of courage is fair.

Graded absolutism

This section is going to be the most theological of the bunch. If you’re not Christian, you’ll have to forgive the heavy biblical references. But you might be comforted by my critiques of mainstream Christianity.

Without further ado, what’s graded absolutism?

From Wikipedia:

Graded absolutism is moral absolutism but qualifies that a moral absolute, like "Do not kill," can be greater or lesser than another moral absolute, like "Do not lie".

With Nazi at the door, there is something more valuable than truth, and that’s survival. Graded absolutism doesn’t just tell us that there are virtues to strive for, but that some have higher value than others.

I’ll submit that Jesus was a graded absolutist. In fact, I’ll even say one of his primary critiques of the Pharisees is that they weren’t.

Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets. I have not come to abolish them, but to fulfill them.

Matthew 5:17

Most preachers will say that Jesus came and paid for our sins and by doing this he fulfilled the law. In the Old Testament, God laid down many laws. And after Jesus, all those laws have been done away with. After all, don’t Christians eat pork? “Abolished” sounds pretty accurate, so why is Jesus insisting this is not what he’s doing?

Einstein didn’t make Newton go away. At the human scale, Newton is still king, but if we want to explore the galaxy, we need Einstein. Discovering a fuller truth doesn’t make the lower resolution truth false. Instead, it fills out the truth that was already there. In the original Greek, “fulfill” means to fill up, to complete, etc (source). The idea wasn’t that eating pork was bad and now is good. Instead, the idea is that the injunction against pork was important but that more important rules supersede it. Or even that some rules were useful for what they did, but technology makes previous concerns moot.

The concept of graded absolutism isn’t complicated. We understand the idea that some crimes are worse than others. We understand that when circumstances change, we should also chance our responses to these circumstances. We also understand that intention is important. Someone might technically be doing good because he has to, but his intentions could be awful.

The problem, I argue, is that mainstream conservative theology has fallen into the same tempting pit that Jesus accused the Pharisees of.

Many Christians will read “unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” and then explain this is why we need the blood of Christ to wash away our sins since we’ve all told white lies. They’re getting lost in doctrinal logic, and completely glossing over Christ’s own words.

Jesus doesn’t mean exceed as in being more fussy about the finer points of the law than the teachers of the law. He’s making a different point altogether. He goes on to talk about intention. If you’re lusting, then you’ve committed adultery in your heart, etc. So it’s not about following the law more strictly, but about setting your heart in the right place. We could say direction is more important than position.

The problem was that the Pharisees were concerned with trifles at the expense of more important things. Should you lie to the Nazi at the door? Should Christians get piercings, or tattoos? That’s the key to being better than the Pharisees. Many of the worst evils are not evil in themselves, but they are evil when they take precedence over something more important. It’s about focusing on a speck in someone’s eye when there is a long pole sticking out of your own eye.

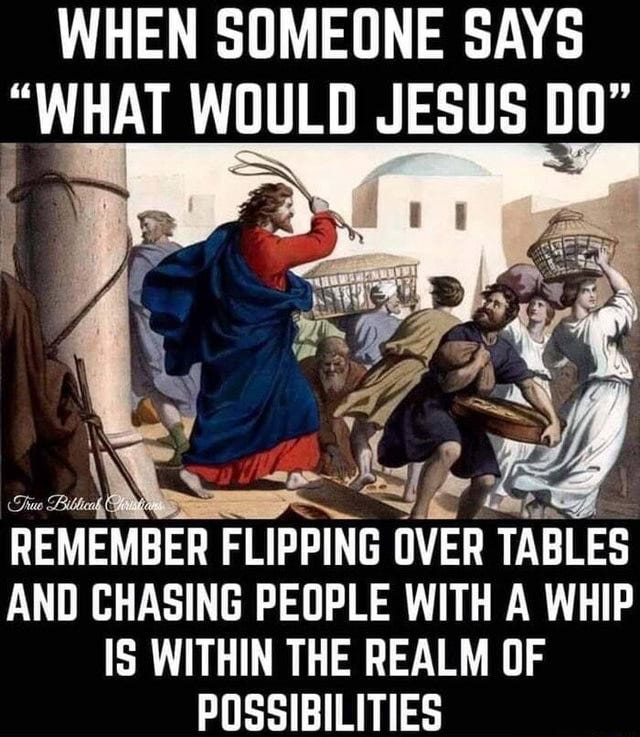

Graded absolutism does come with some problems: how do you decide which moral principle is higher or lower than another? It’s difficult, and you can get it wrong. If you go by Christ’s example, flipping tables is acceptable under the right circumstances.

Modern Christian conservatives would claim that rule of law and destruction of property are not valid forms of protest. Fine, but what about destruction of church property? This is the iconoclast’s instinct. The Protestant Reformation, after all, was destructive and bloody.